Now that I've finished my work researching the Southern Cone countries of Chile and Argentina, I suppose it's time to discuss Bus Rapid Transit - in particular, operational styles and a comparison against rail.

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) is, in its simplest form, a surface transit route using vehicles that are unguided (but can be guided on certain portions of their route) but have their own dedicated right of way, and usually have additional features including but not limited to platform level boarding, transit signal priority, and/or off-board fare collection. The most common alignments are in medians or along dedicated bus-only roadways, but other alignments exist (e.g. if a road has a service road, aligning it to the dividers - very popular in China with its massive arterials).

Paseo de la Reforma on Metrobús Line 7 [Google Streetview]. An example of a BRT corridor using the outer curb on a boulevard with a service road.

Most features of proper Bus Rapid Transit aim to improve speed and reliability. Dedicated lanes ensure that private vehicles do not get in the way of high capacity buses. Putting them in the median or in a bus-only roadway ensures that they do not run into conflicts with turning vehicles and curbside uses (in most cities, it is legal for vehicles to park in or stop in dedicated bus lanes, making them mostly useless). By grade separating intersections, preventing turns across the busway, and/or providing signal priority/queue jumps, buses do not have to stop or slow down at intersections. Off-board fare collection allows passengers to board at any door without having to line up - this is a significant time saver over the course of a long journey. And platform level boarding provides accessible access while also speeding up trips due to faster loading times. Even a subset of these bus priority features allows for time savings - not having to deploy wheelchair ramps and not having to wait for people to fumble with a cash payment at the front of a bus while blocking everyone behind them saves time and makes service much more reliable.

Aero Peoria in Tulsa [Google Streetview] and ORBT Dodge in Omaha [Google Streetview]. While there is no dedicated ROW, signal priority and platform level boarding help keep buses moving in these Arterial BRT lines.

Now, it is important to note what is and is NOT BRT. BRT is a spectrum and there is no good dividing point - the ITDP BRT Standard is the best tool we have as of writing. Some services may be branded as BRT but have no dedicated lanes, or may only have curbside lanes - this mixed traffic operation means that buses are susceptible to traffic. This is very common in the USA, since the FTA allows for bus priority to be branded as BRT ('corridor based BRT' vs 'fixed guideway BRT'). We call this Arterial BRT on the MRA using language adopted from the Transport Politic which is currently used officially in cities such as Minneapolis. Then there is the opposite - dedicated lane bus systems with almost none of the other features - in some cases, trying to call these BRT is very difficult because they meet the minimum standards for BRT but do not look or feel like a BRT system. The best example I can find is Av. Sul in Recife - while the Via Livre BRT system looks and feels like a high quality system, Av. Sul is an open busway with not much more than poles for stations, no safe way to access stops in the eastbound directions, etc. Yet it has almost no intersections and so the buses speed down the ROW with reliable service. Elsewhere in Brazil, there are plenty of median bus lanes where none of the other BRT features exist. Of these, Juiz de Fora seems to be the only case where it passed the BRT standard minimums (by cutting off intersections) - most other systems do not even do this much and so are considered BRT-Lite on the MRA. This term is usually used to encompass all systems below BRT standards but we use it specifically for this case.

Loop Link in Chicago. A good example of a BRT-Lite open busway. Vehicles can cross the lanes to turn, and although there are dedicated lanes throughout the small system, there is no off-board fare payment and intersection priority is provided only via queue jumps as the streets the system runs on are not major enough to support intersection priority without impacting other bus routes going north-south.

Now, the meat of this blog post - network design and operational patterns, and when NOT to use Bus Rapid Transit.

First, a brief overview of BRT's benefits and downsides when compared to other transit modes. The main benefits are low implementation cost and operational flexibility. The main downside is limited capacity per vehicle (and therefore higher maintenance costs and operational costs due to needing more drivers than rail to carry the same number of people). There are other issues with buses as well - most of the time they pollute the corridor with fumes and tire particles, and they wear out their rights of way very quickly - especially around stations and intersections where vehicles start and stop at roughly the same location over and over again (either high maintenance costs, or high upfront capital costs to use reinforced concrete/more sturdy materials).

Estrutural Leste in Uberlândia [Google Streetview]. Due to not using sturdy materials at stations (with set stopping location due to platform screen doors, combined with frequent stopping and starting), noticeable ruts have been created in the asphalt where the wheels are located when a bus is stopped at the station.

Let's dive into that 'operational flexibility' portion though. The main benefit can be stated as such - buses can leave the BRT corridor. In other words, you can build BRT infrastructure but run a bus beyond the infrastructure. A major benefit of this is that you can build some BRT infrastructure now to get benefit, and then build further when you have the money for it. This is NOT the case with a rail system where you must lay rails/guideway/signaling along the entire route to support service, and where only building a short chunk of infrastructure on its own (including the OMF) may not be financially viable. In addition, buses can use passing lanes to bypass stations at the cost of space - doing this with a rail or other guided system is very expensive due to the need for physical switches on the ground. In fact, I'd say that if a BRT system does not make use of either of these two benefits, it should not be built as a BRT system and should instead be a rail system - especially for systems that are fully grade separated and should just be built as light metros or metros since grade separated stations and guideways form the bulk of the capital costs. Fully closed BRT systems without passing lanes that try to mimic a rail service with buses in order to save capital costs do exist and it's not uncommon for them to either do poorly if their feeder systems are lacking (Hanoi BRT01) or blow past their capacity (CDMX Metrobús Línea 1).

This leads into the corridor structures used by BRT - trunk-only, trunk-feeder, partially open, and fully open. Trunk-only and Trunk-feeder systems have services that only run on the BRT infrastructure, forcing transfers for anyone going past the BRT infrastructure. Partially open systems have core routes serving the bus rapid transit infrastructure but have vehicles that can leave the corridor in order to offer one seat rides. And fully open systems may not even have routes that serve all the stations. Of these, the first two are the ones often pitched as an alternative to more expensive rail systems. The latter two make use of BRT's strengths as a mode but are not always even branded as BRT, especially for fully open systems.

Let's discuss the operations of these four types of BRT. For each, I will provide good and bad examples.

Trunk-Only - a rail style service where there wasn't enough money or passenger demand for rail - sometimes both. In a trunk-only system, the services on the BRT corridor are the only services on the BRT corridor, and although the BRT services may continue past the corridor, no other buses use the corridor. The Healthline in Cleveland is a formerly excellent example of a successful BRT service that has since had most of the BRT features cut to the point that if the platforms hadn't been level, it would have been kicked off of the list of BRT systems. Other good examples are the UVX in the Provo-Orem area and most of the Metrobús lines in Mexico City. Poor examples include the fully grade separated BRT Sunway line in the Kuala Lumpur metropolitan area (built poorly and with exorbitant fares) and the Multan Metrobus in Pakistan (no network effect; route duplication and lack of feeders).

Trunk-Feeder - ripe for rail conversion. In a trunk-feeder system, BRT services run exactly the same as on a trunk-only system, but tend to either stop at or terminate at massive integrated terminal facilities where passengers can transfer from feeder services onto BRT services. These have a few major benefits over trunk-only services - first, the feeders ensure that the scope of the BRT infrastructure is felt across the region and provide ridership, and second, this model works really well for providing a good foundation for future rail services as well by building up ridership. It is therefore a viable 'first step' to a higher capacity route, and works well in mid-sized cities. In large cities, however, passenger demand is likely to exceed the capacity of the core BRT corridor. Good examples include Optibús in León, and TransCaribe in Cartagena, while Barranquilla made the questionable decision of placing the Estación Retorno Joe Arroyo halfway down Carrera 46, forcing most passengers in the northwest part of the city to take a feeder in mixed traffic to a BRT service that they only ride for a few stations.

Partially Open - best of both worlds, taking advantage of what makes BRT good. In a partially open system, while core routes exist that serve the BRT infrastructure, most or all services leave the busway to travel elsewhere, offering one seat rides. Cali's MIO is one of the best examples of this. Bogotá's TransMilenio also switched to this model. It's actually hard to find truly bad examples of a partially open system, unless you count the decidedly not-BRT rapid bus network in Tijuana.

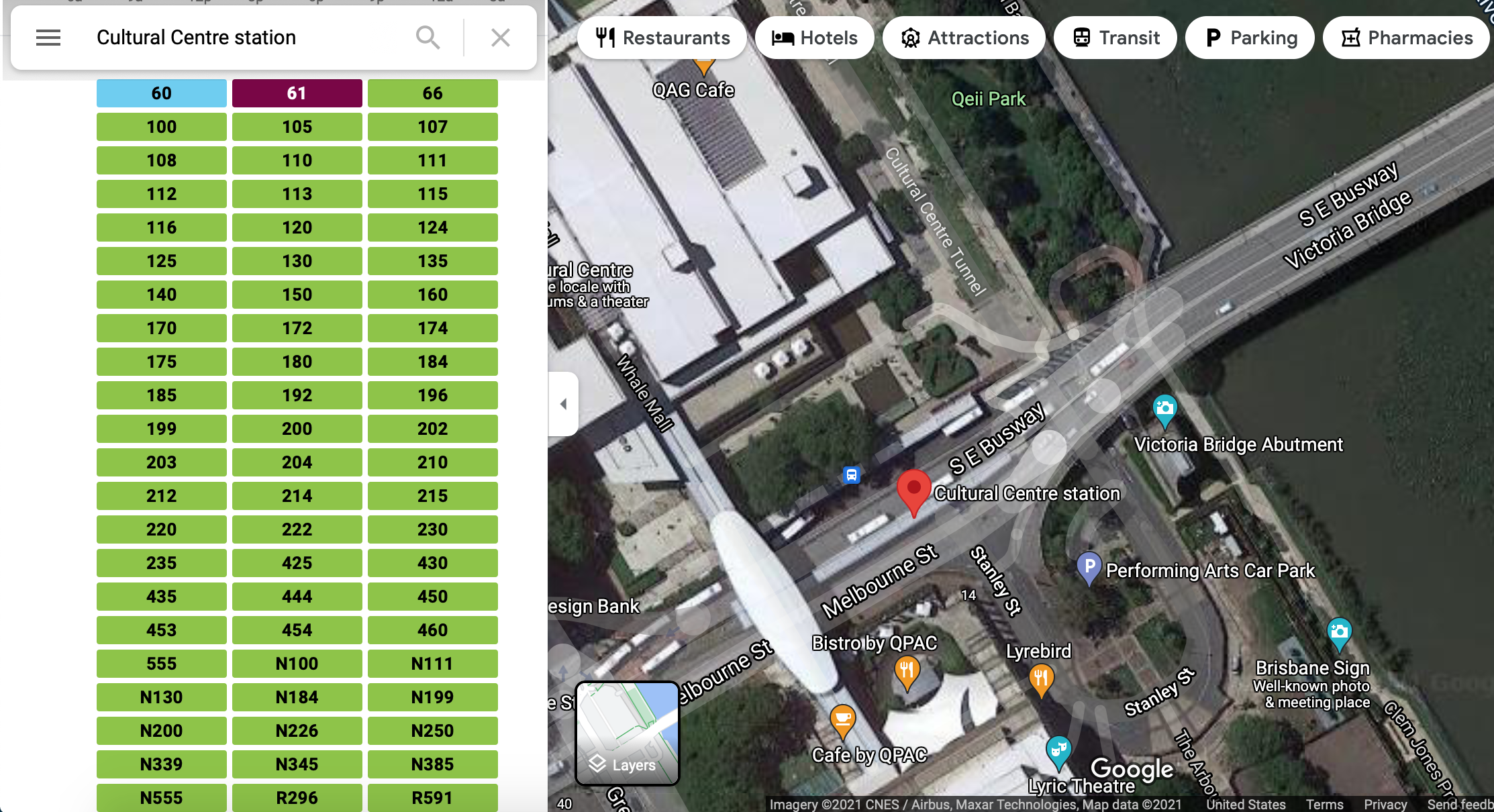

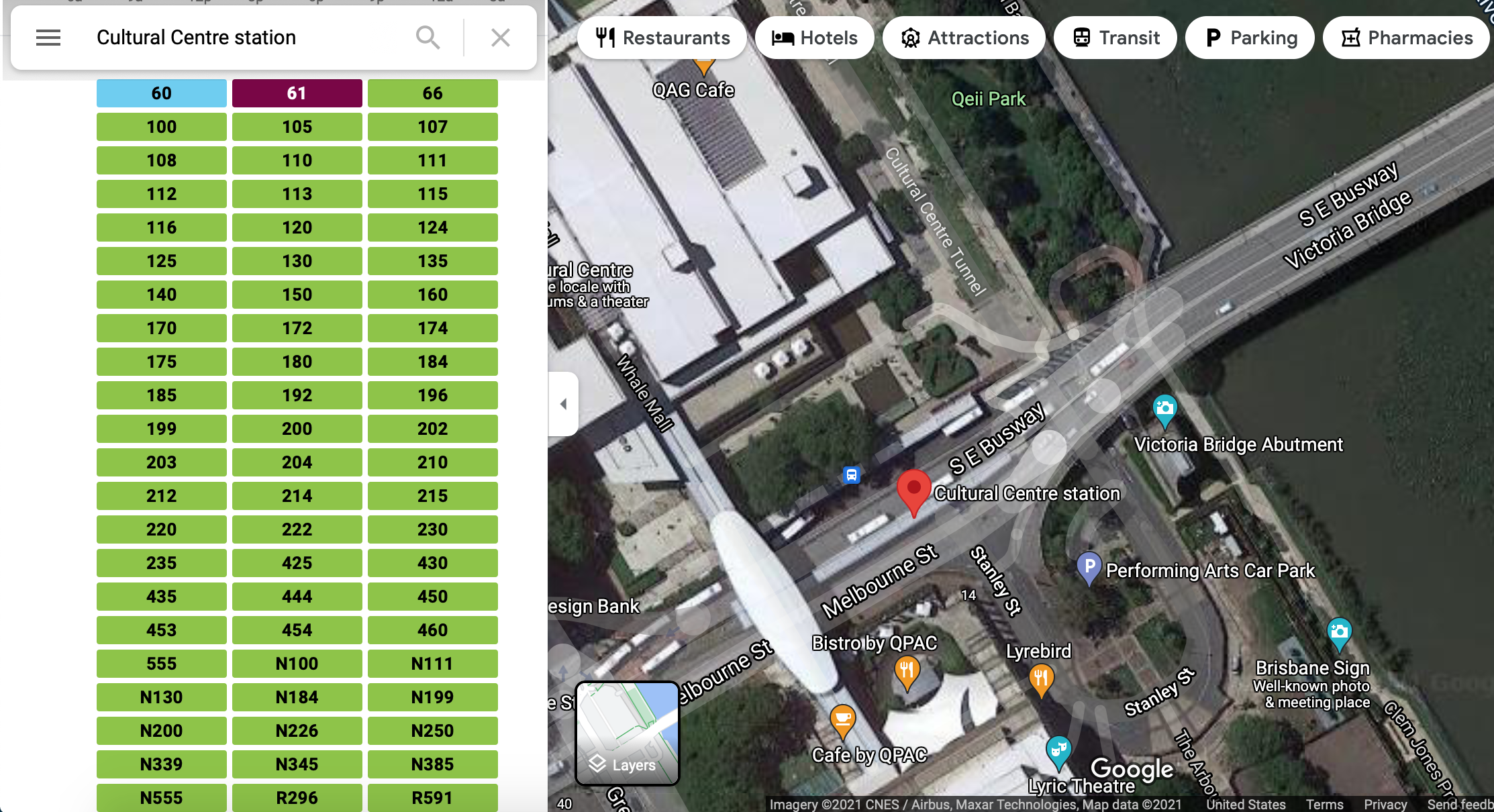

Fully Open - fundamentally different from rail style service. In a fully open system, there are no core routes, and there is often no system branding. It is simply infrastructure for fast and reliable bus service, with buses using the infrastructure as convenient. A single corridor may have dozens of routes as in Brisbane's Busways. Buses may enter and leave the busway infrastructure at will as with BRT corridors in Santiago and Buenos Aires, which are fully open and do not usually have a single route that actually serves all stations in the corridor. Heck, some services frequently serve stations in a single direction only. Frequencies are typically measured in the seconds, and in some systems with no BRT-specific branding on vehicles, the infrastructure may actually become invisible to the users of the system, such as in Santiago with its uniform bus priority across the city. The use case for these corridors should not be to replace rail but instead to offer an efficient one seat ride for users of bus routes that happen to use a corridor for part of their route - for this reason, multiple disconnected open BRT corridors are viable and even encouraged (though linking them up improves the network). In North America, new examples include the Van Ness Rapid in San Francisco and the Columbus Avenue Busway in Boston, both of which are more similar to open busways in Buenos Aires than they are to the AC Tempo or Silver Line in their own metropolitan areas. But it is worth mentioning that while these systems can be very beneficial, it is important to not repeat the mistakes of Brazilian BRT-Lite - high vehicle counts result in noise and pollution along a corridor, and since not all buses are guaranteed to stop at all stations on the corridor, the systems can be hard to understand. Brisbane is by far the worst offender in this case, with so many different infrequent one seat ride services that trying to get between stops on the busways is actually impossible to do effectively without an external trip planning tool.

Brisbane Cultural Centre Bus Routes. It can be hard to navigate the system when so many services stop at a given location. Brisbane is currently looking into new 'Metro' routes which will immensely improve wayfinding on their busway network and make it much easier to understand the core part of the network.

Bus Rapid Transit offers a variety of different benefits as part of an integrated public transportation network owing to it flexibility as a mode. But it is not a direct replacement for rail, and although it can sometimes work in similar situations, in order to take advantage of its benefits it should not be operated like a rail service. There's a lot more to discuss, but for now, we'll leave it at that.